Seeing What Hurts: Habakkuk, Suffering, and the Prayers God Doesn’t Answer the Easy Way

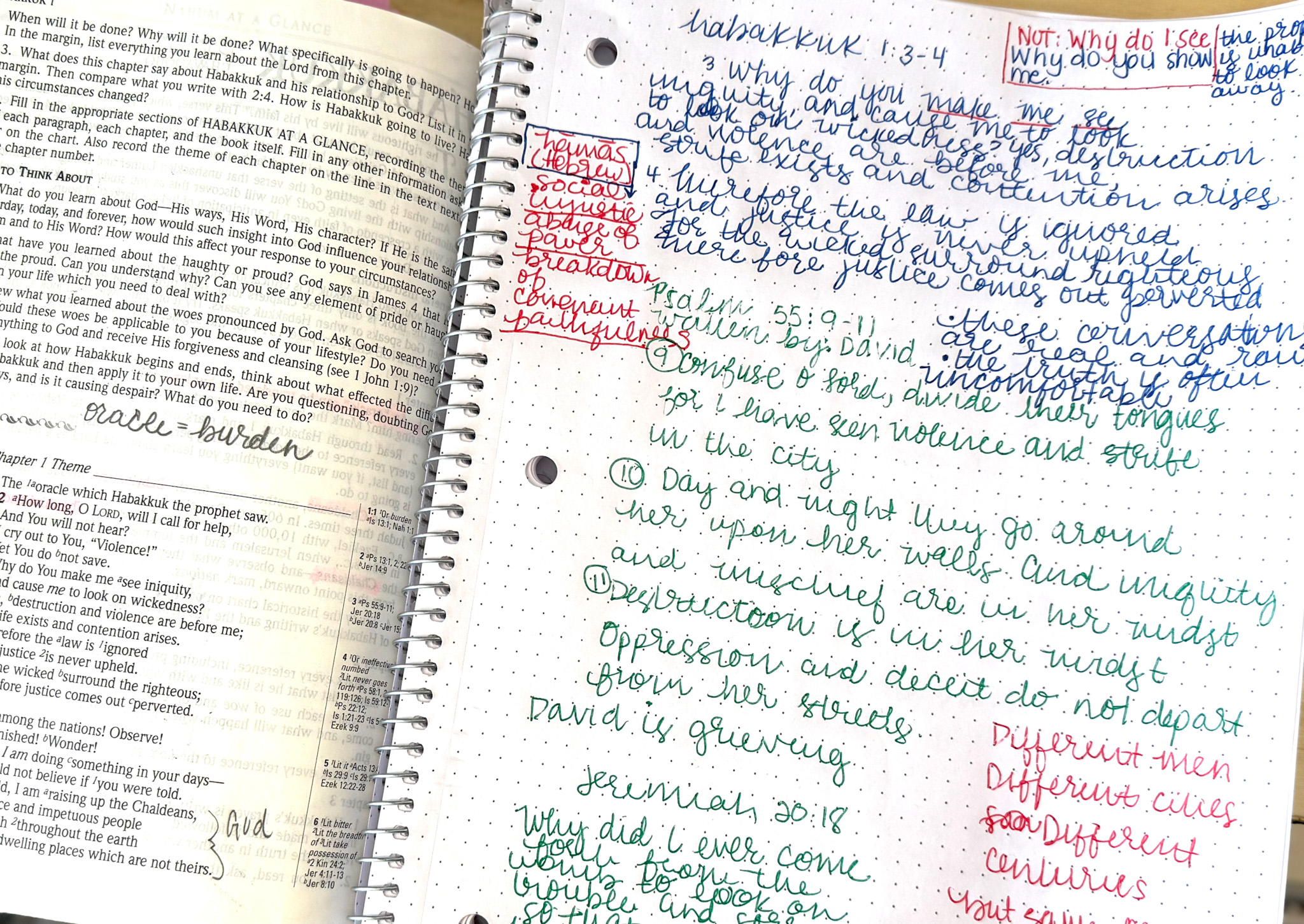

I have been studying Habakkuk. On the first day, I studied Chapter 1, and now I am going through it verse by verse, one day at a time—not religiously, just when life allows for the quiet.

If you want to catch up to today, you can click here for Day 1 and here for Day 2.

Today I sat with Habakkuk 1:2–4, and what struck me most was not the harshness of the words, but the selflessness of the prayer.

Habakkuk isn’t starving.

He isn’t imprisoned.

He isn’t begging for personal relief.

He’s asking God a question that hurts precisely because it isn’t about him:

Why do You make me see iniquity,

and why do You look upon wrongdoing?

Destruction and violence are before me;

strife and contention arise.Therefore the law is paralyzed,

and justice never goes forth.

For the wicked surround the righteous;

therefore justice goes forth perverted.

The “violence” Habakkuk describes isn’t just physical harm. It’s corruption, injustice—systems that crush people, courts that fail, and power that protects the wrong people.

Side note: The Hebrew word for this type of violence is ḥāmās.

Habakkuk isn’t asking God to comfort him.

He’s asking God to fix a broken world.

And that is precisely the distinction that stuck out to me.

Sometimes the hardest suffering isn’t what happens to us; rather, it’s what we’re forced to witness and cannot forget—while being simultaneously unable to control or fix it.

When witnessing suffering breaks your faith

I know that feeling.

On November 1, 2023, I was lying in bed in the dark, with folded hands and a formal reverence for prayer, asking God that my dad’s biopsy would come back negative for cancer. I wasn’t expecting an answer right then.

Minutes later, at 11 o’clock at night, my dad texted.

Not because he had gone to the doctor that day.

Not because we were expecting news at that exact moment.

But in what could only be described as divine timing, he had randomly checked his patient portal—at the exact time I prayed—and saw the diagnosis: metastatic malignant melanoma.

He didn’t know what that meant, so I had to call him and explain it.

The timing felt cruel—surgical, almost too precise.

I couldn’t understand why God would do that. Why not answer the prayer the easy way? Why not build faith by preventing suffering?

A couple of weeks later, I checked my dad’s patient portal myself before his appointment and discovered the cancer had invaded every organ in his body except his brain. I was at work. I threw my computer down and cried in my office for three hours. I could have gone home since court was over for the day, but I couldn’t drive.

I decided not to tell my dad. I would let his doctor explain it—without emotion. I couldn’t be the source of that news. But then my dad texted, “Can you call me and explain this report?”

The report was written in scientific language. As a medical-malpractice court reporter, I didn’t need a dictionary to understand what it meant. Pulmonary (lungs). Osteo (bones). And more.

My dad got very sick. He lost over 50 pounds. He was hospitalized multiple times. There were moments when it felt like we were close to losing him.

He was 57 years old.

And I struggled—not just with fear, but with trust. God suddenly felt less safe than I had believed.

Faith that grows in places I never would have chosen

A year later, my dad went into remission.

Around that same time, in November 2024, one of my dogs went missing. My dad had flown in from Florida, and we spent the day driving around together in my Jeep looking for her.

I told him I expected she might be hurt—she had never wandered for that long—but what I needed most was closure. I needed to know she wasn’t suffering somewhere alone.

The timing of it all felt strange and tender. My dad and I are both dog lovers. He owned her sibling. And we don’t often get long stretches of time like that together—Jeep top down, sunny, seventy-five degrees. It felt like a moment made just for us.

As we drove, I told him the truth. My faith had shaken during his illness. I felt confused. Angry. Disoriented.

And he said something I wasn’t expecting.

He told me his faith had grown during that time.

Not because he suddenly became religious or started going to church—but because when everything else was stripped away, he had to believe God was real. He had to trust God with his life, whether he lived or died.

He said he was thankful for the life he had—even if that season had been the end of it.

Then he said something quietly confident: that he believed we would find my dog, or at least get the closure I needed.

He wasn’t wrong.

We found her. She had been hit by a car.

It wasn’t the ending I wanted—but it was the one I needed. No imagining. No wondering whether she was suffering somewhere unseen.

I got to grieve what actually happened, not what my fear invented.

The prayer I didn’t know I was praying

Looking back, I don’t think God ignored my prayer about my dad.

I think He answered a deeper one.

If God had prevented my dad’s illness, my dad would have missed something essential—something his soul needed for the rest of his life. A kind of faith that only grows when there’s nothing left to hold onto.

That’s hard to admit, because it means beneath my prayer for healing was something else:

God, don’t let this cost him anything.

God, don’t let his faith have to grow this way.

I didn’t mean that—but that’s what the prayer amounted to.

Why Habakkuk feels so personal now

Habakkuk’s prayer isn’t about personal suffering. It’s about the pain of watching others suffer while knowing God could intervene.

That kind of pain is deeply emotional. Deeply moral.

Sometimes witnessing suffering is harder than suffering itself.

Habakkuk teaches me that it’s okay to say that out loud to God—because it’s honesty. It’s a relationship. Not some ironed-out Christian dialogue.

The Bible doesn’t shame that kind of prayer.

It preserves it. It even highlights it in Jeremiah and the Psalms.

And that tells me something important.

God would rather have our raw, confused, aching prayers than our polished silence.

Where I land (for now)

I don’t have a tidy conclusion.

Habakkuk doesn’t either—at least not yet in 1:1–4.

What I know is this:

God doesn’t always do the easy thing.

But He doesn’t waste suffering—especially the kind that grows faith, compassion, and truth.

And sometimes the prayer God answers isn’t the one we knew how to pray.

But it is the one our hearts needed all along.

Leave a Reply